A conduct of inquiry.

If you are anyone claiming to have genuine curiosity about the world you are naive to reason about things without wondering what it means to reason. What reasoning tools exist, are they good? What assumptions do it make? What does it mean to know something? I often tell people that some philosophy needs a warning sign. Once an idea gets a foothold in your mind you cannot unthink it. This proverbial toothpaste doesn't go back in the tube.

Trusting your senses

Naively the first thing people assume is that they can trust their senses. Historically philosophers once thought the same and dubbed this epistemic philosophy Empiricism. The problem with empiricism is that it is sometimes the case that our senses deceive us. We touch, see or hear something that is either not there, or is not able to be perceived by others.

Brain in a Vat

The modern version of Descartes's "evil demon" tricking your own mind. There is an old thought experiment in which one attempts to argue that they are not a brain in a vat. The brain here is removed from the body and kept in a nutrient dense vat, connected to a supercomputer that generates sensory experiences for you that emulate a normal life. The Matrix paints more color to the same idea here. There is merit in painting skepticism against your own experience. In fact this phenomenon can be traced to the many ways people personify the devil in Judeo-Christian religion. Surely not all abstract ideas are demonic. But Empiricism cannot express objective abstract ideas. How can we measure morality, mathematics, or concepts with our senses? Empiricism provides no insight to explaining the experience of cognition.

However there are also more concrete counterexamples. For example the Young and Old Woman.

Some people look at this image and see a young woman. Others see an old one. If you look at the image long enough you may be able to see both. It seems that either our senses are unreliable oracles for an idea of reality, or there is no such thing as an objective reality.

The Scientific Method

Most people's first encounter with the scientific method is a bit authoritative. "Here is how you do science!" not a "how can we know things". To me this seemed like the next best place to look for ways in which people know things. After all, scientists claim to know things, or society seems to believe they do.

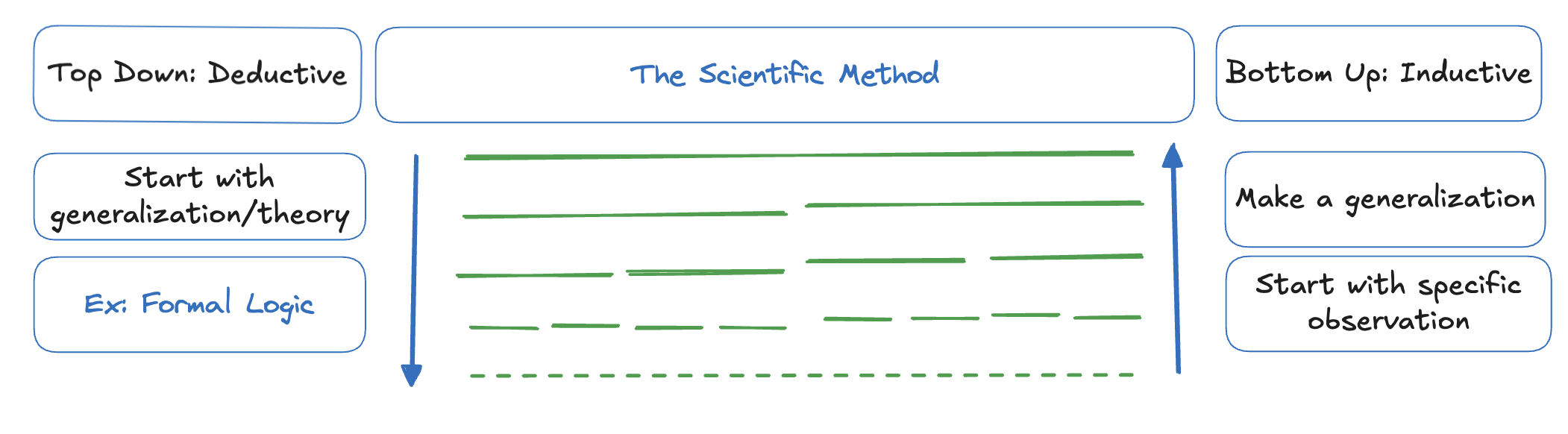

When you break down the scientific method it stands upon the shoulders of two types of epistemic reasoning, Inductive and Deductive reasoning. Induction is a bottom up method for pattern recognition to form generalizations. Deduction is a top down application of generalizations.

Inductive Reasoning

Induction is the process of drawing general theories from specific experiences. This is what people call the inductive step in the scientific method, when you form a hypothesis. The logic goes as follows: Observation -> Conclusion. For example:

- Observation: I have met a friendly person

- Conclusion: all people are friendly

This now gives us the ability to form some abstract relationship from experiences to ideas. However as you can tell induction is necessary but not sufficient to reason about objective knowledge. In fact, as said in David Hume's Problem of Induction, just because something has happened in the past is in fact not a good enough reason for it to happen in the future. How can we justify believing future experiences will resemble past ones, or that our senses are reliable guides to truth, without appealing to reason beyond experience?

Deductive reasoning

Deductive reasoning is the process of applying a generalization to a specific problem, often to learn about something specific. Anything with the structure If X then Y is deductive reasoning where you are applying X to Y. For example, mathematics is deductive as well as formal logic. In fact there is a result known as the Curry-Howard isomorphism showing that math proofs and computer programs are equivalent. The problem with deductive reasoning is twofold:

- You depend on an assumption somewhere (initial assumption X)

- Everything can be either true or false

Gödel's Theorem of Incompleteness

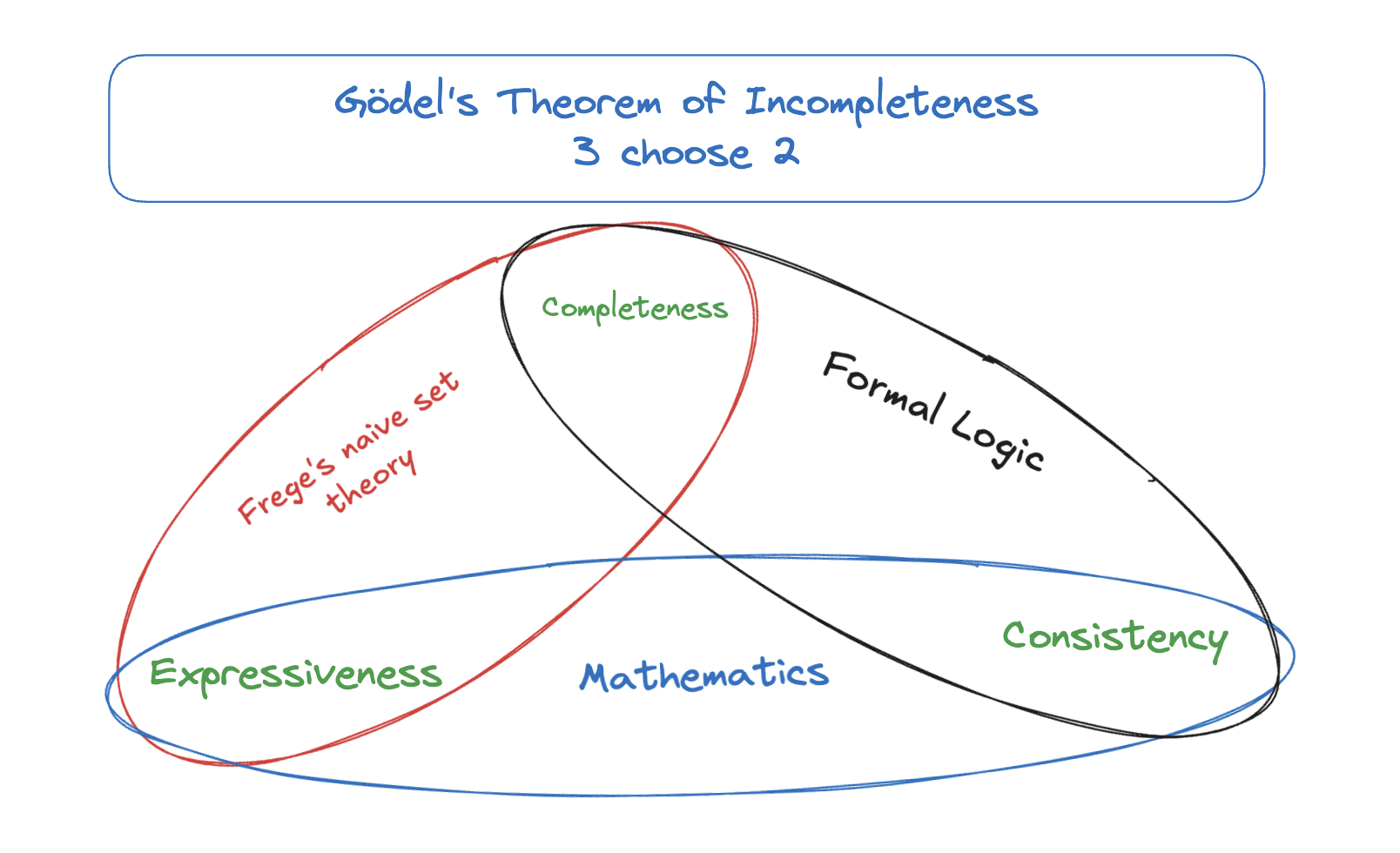

Gödel's theorem of incompleteness is a fantastic meta result that defines the limitations of formal languages of reasoning. Most all explanations of the theorem I have come across have been verbose requiring lots of prior knowledge. An intuitive way to describe the result of the theorem, not the proof, is to think of it as a trilemma where there are three properties any such language may have and you can only pick two of them.

The properties are:

- Consistency: Doing the same thing gives the same result

- Completeness: Every true or untrue statement is provable

- Expressiveness: Defined by ability to encode natural numbers

These are perhaps interesting results because they are restrictions on our ability to formally reason about objective truth at all. Pure induction is just perceptive pattern matching and has no semantically defined rules and thus cannot be a language of reasoning. There do exist some inductive languages of reasoning that do depend on deduction for example Bayesian inference or Solomonoff induction.

Because of these fundamental limitations in a unified theory of knowledge that are all independently crippling, really truly having any objective knowledge is fundamentally very difficult. It would be very bold of me to claim knowledge of much of anything. Perhaps the only thing I can say with confidence is that what you believe determines your experience of the world.

The Yoneda Lemma

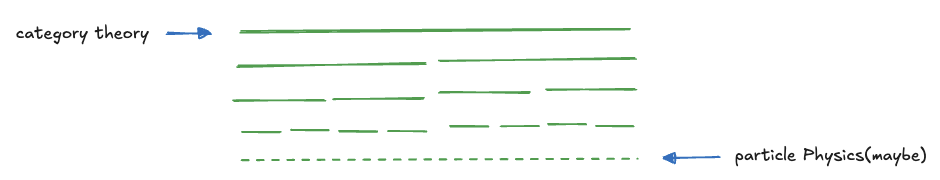

One of the most compelling results in epistemology comes from a type of mathematics called Category Theory. Category theory is interesting because it is defined as the most abstract type of mathematics.

When things are abstract they generalize and are often more useful because they apply to all the things they generalize. For example it's more useful to know something about all numbers than a specific number.

However category theory is not just the most general theory of mathematics, it is the most general theory, period. So results in category theory apply to, well, everything. As a result of how powerful category theory is, it is actually pretty hard to make new results in it. You can see category theory come up everywhere; it is in some sense a collection of the most useful patterns in the world.

The Yoneda lemma states that all properties of all objects are defined by their relationships to other objects. Put simply, ontology is bullshit, there are no ontological (inherent) properties of anything at all. Everything is interdependent. If an object lives in a vacuum it is defined entirely by its relationship to the vacuum and now both our perceptive relationships to the idea of this object.

Interestingly this is the same view of Tibetan Buddhism. That everything is defined entirely by its relationships with everything else. This result supports a subjective relationship dependant epistomology not one of an objective truth.

This is a powerful result because it rests only on the axioms of mathematics, often formally referred to as the Peano axioms. That isn't to say mathematics is perfect; in fact there are paradoxes in mathematics like the Banach-Tarski paradox, or Russell's paradox. But it does rest on the same foundations that most modern science does.

Often when we encounter a paradox the academic thing to do is to put pressure on the assumptions that led us there. The assumption the Banach-Tarski paradox puts pressure on is the axiom of choice. However you also need the axiom of choice for measure theory, which you need for quantifying anything. Knowledge and reasoning is about a tradeoffs of beliefs. What you believe determines your reality.